In its heyday, in the 9th century, Ireland was churning out books and monks in equal numbers, re-christianising dark-ages Europe

In its heyday, in the 9th century, Ireland was churning out books and monks in equal numbers, re-christianising dark-ages Europe (see 'How the Irish Saved Civilisation', by Thomas Cahill).

Unfortunately for us many of the trappings of that immensely rich christian era have not survived to today. We lost a lot of our religious shrines, relics and artifacts when the Vikings raided our monastic settlements in the 9th and 10th centuries. They were plundering for low-hanging fruit and Ireland was an orchard of same for them. While monasteries and abbeys were generally under the protection of the local Irish chieftain or king, there was no natural enemy, save a local dispute and indeed many inter-Irish rivalries resulted in raids that were focussed on plundering the wealth of our own abbeys and convents, just as the vikings did.

Unfortunately for us many of the trappings of that immensely rich christian era have not survived to today. We lost a lot of our religious shrines, relics and artifacts when the Vikings raided our monastic settlements in the 9th and 10th centuries. They were plundering for low-hanging fruit and Ireland was an orchard of same for them. While monasteries and abbeys were generally under the protection of the local Irish chieftain or king, there was no natural enemy, save a local dispute and indeed many inter-Irish rivalries resulted in raids that were focussed on plundering the wealth of our own abbeys and convents, just as the vikings did.  The Vikings were indiscriminate, opportunistic raiders, taking plunder in every form, from portable treasure, to irreplaceable books, to hostages and slaves. Mind you, lest you think we Irish were all saints, many Irish under-lords were no better in their day, striking terror into the villages along the Welsh coast in the 5th and 6th centuries, enslaving their captives, including one rather famous one, St. Patrick.

The Vikings were indiscriminate, opportunistic raiders, taking plunder in every form, from portable treasure, to irreplaceable books, to hostages and slaves. Mind you, lest you think we Irish were all saints, many Irish under-lords were no better in their day, striking terror into the villages along the Welsh coast in the 5th and 6th centuries, enslaving their captives, including one rather famous one, St. Patrick.

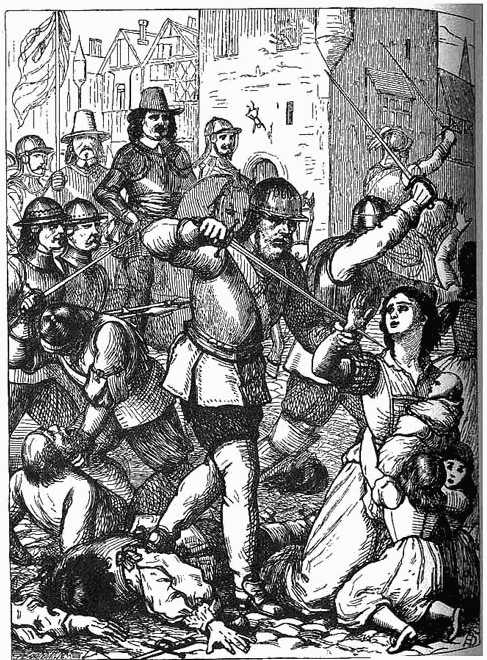

We lost even more of our ecclesiastical treasure during the reigns of Henry VIII, Elizabeth I, James I and Charles I. Monasteries with their fertile land, fish-filled lakes and brimming coffers became targets for opportunistic soldiers and civil servants in the enforced dissolution of the monasteries, destruction of the mother church and introduction of the new, imposed state-controlled established church, anglicanism.

Then finally, in the late 17th and early 18th century, came the total destruction of the old Irish order and our unique dare I say it, the non-European system of government, alliances and land use, all swept away by the English resulting in the killing of half the population in war and famine, the confiscation at gun-point of all the lands of Ireland, the destruction of the old Irish agricultural system based on cattle, the enclosure of our fields for cultivation and rent, and finally, he slaughter of the relics, in a systematic and deliberate theft or destruction of the symbols of our christianity, idolatry to the invader, during the Cromwellian and Williamite pogrom, leading to the complete subjugation of Ireland to British Rule, and including the complete proscription of the Catholic religion during the Penal Laws.

What had survived through the earlier difficult centuries with the help of Irish and Norman patronage, was now swept away entirely, lost forever, our past glory, gone, without trace. Churches allover Ireland burned, stripped of their glass and lead and timbers and carvings. A thousand years of Irish christianity and all that was associated with it, demonised, destroyed, stolen, eradicated.

Yet, despite these incredible odds, some church artifacts have survived, showing us just exactly how incredibly sophisticated and learned were our fore-fathers.

The Book of Kells, The Cross of Cong, the Ardagh Chalice, St. Patrick's Bell, and so many more gloriously executed items that survived, and now define our past relationship with God. Some were plundered, but survived being broken up, or melted down. Some were hidden in churches and homes, protected from destruction, but cosseted from view. Others were lost, perhaps in times of danger or attack, or simply hidden and mislaid. Either way, we are fortunate that so much has survived. We can gaze in awe at the astonishing skill and faith of our forebears. The Derrynaflan Chalice is one amazing example.

So also is this item below, the Moylough Belt. Moylough, in the southern part of County Sligo, was under the protection and support of the O'Connors, the last high kings of Ireland and a family who more than many, oversaw the creation and ultimate survival of so much of our church history

Just imagine if you lived in that era. What was Ireland like? Imagine what the people were like? That's the sort of conversation I have with my guests on my Walking Tours of Galway ... and hey, everyday is a school day! (Nah, school was never like this).

Brian Nolan, Galway Walks - Walking Tours of Galway www.galwaywalks.com or @Galwaywalks on Twitter and Instagram

The Moylough Belt

"Dating from the 8th century AD, the Moylough belt shrine is one of the great treasures of early Ireland. Fashioned out of bronze and silver, it was found in 1945 by Mr John Towey as he dug turf on his father’s farm at Moylough, Co. Sligo. Slicing through the soft peat, he unexpectedly hit something hard at depth of c. 4 feet below the surface. Presuming it was a large stone, John bent down and cleared away the soil with a small garden trowel. To his amazement, what was revealed was not a stone, but instead, a glistening, metallic object. The Moylough belt shrine had been discovered.

"Dating from the 8th century AD, the Moylough belt shrine is one of the great treasures of early Ireland. Fashioned out of bronze and silver, it was found in 1945 by Mr John Towey as he dug turf on his father’s farm at Moylough, Co. Sligo. Slicing through the soft peat, he unexpectedly hit something hard at depth of c. 4 feet below the surface. Presuming it was a large stone, John bent down and cleared away the soil with a small garden trowel. To his amazement, what was revealed was not a stone, but instead, a glistening, metallic object. The Moylough belt shrine had been discovered.

The belt consists of four bronze segments, each of which enclose a strip of plain leather. The bronze sections are richly decorated and are also hinged together, so that the components are flexible. This means that the belt could, if desired, be placed around the waist. Indeed, wear patterns visible on its surface suggest that it was often worn/used.

Each of the bronze segments contain a centrally placed medallion featuring a ‘Celtic cross’, while their ends are further ornamented with panels of stamped silver foil or openwork bronze. The most elaborate decoration is seen on the two front segments, which take the form of a false buckle and buckle plate. These are embellished with silver foil, glass and enamel, as well as animal and bird head motifs.

This beautiful artefact more than likely represents a shrine that was specifically made to encase the leather segments. It is these simple leather strips then, and not the costly casing, that are the real treasure. They were probably associated with a local saint and must have been important relics to have been so richly adorned.

Photos: National Museum of Ireland

Sources

Duignan M.V. in O’Kelly, M. J. 1965 ‘The Belt-Shrine from Moylough, Sligo’ in The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Vol. 95, No. 1/2, Papers in Honour of Liam Price.

O Floinn, R. 2003 ‘The Moylough Belt-shrine’ in J. Fenwick (ed.) Lost and Found, discovering Ireland’s past, Wordwell, Bray"